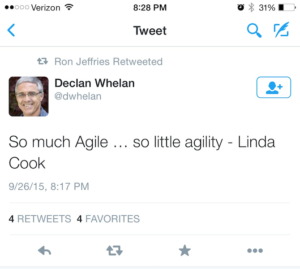

I see development teams struggling with the question – is this a bug, or an improvement. A team that is agile (exhibits agility) would not care.

All the same to me

Tickets come my way. Some are labelled bugs, and others, improvements. To me, whose only mandate is to get the damn work done (aka agility), they all look the same. What I do in response to either a bug or an improvement, is exactly the same.

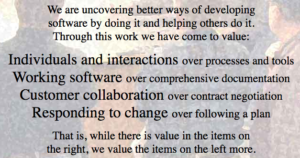

All of the work requires analysis. Gather all of the information that is available (documentation from client and analysts, production data, existing code, other tickets, tests), and separate the essential business requirement from the solution that supports the requirement. Then make sure that all stakeholders (clients, analysts, managers, developers, testers) have the same view of the matter, problem and solution. Often, what they ask for is not what they need, and it is sometimes necessary to improve the solutions they specify. This requires constant and nimble communication. Next construct the solution, which includes testing what we have constructed. Finally, deliver the solution.

Every ticket is this same dance.

Why care, exactly

I can only think of two reasons for fixating on the difference between a bug and improvement.

First, the green-eyeshade brigade use the difference to figure out who to charge for the work. A bug forces the development team to swallow the cost. An improvement can be thrown into the client’s bill.

Second, it might help us figure out who to blame, or to use a more charitable perspective, it might point out where there is room for improvement. A bug implies the developer messed up. In cases where the bug is discovered in production, the finger sometimes points to the tester. An improvement implies the business analyst, or perhaps the client missed something the first time around.

Of the above two reasons, I have sympathy only for the former, the billing problem. This is mostly because I am low on the totem pole, and know very little about money matters. Allow me to punt on this.

The latter reason leaves me cold, as you will see below,

What am I gonna believe – statistics or my lying eyes

Numbers can lie.

It is hard to have faith in statistics that classify work as bugs and improvements, when everyday I see my comrades-in-arms struggle to distinguish between the two. More often than not, we shove tickets into one bucket or the other so work can move on. Typically, some power-that-be is breathing down our necks, or the task management tool is forcing us to make a selection. Come time to review the work, we all know that the pretty pie charts, which the managers pass around, are nonsense.

I don’t need statistics to know the folks that I work with.

I work with business folks, development managers, analysts, developers, testers, tech-writers, and so on. After I spend a couple of weeks in the trenches with them, I know what their strengths and weaknesses are (don’t look now, that’s agility).

Take a developer for instance. I read a developer’s code. That tells me how she thinks through a problem. I know if she can tell a story in simple, straightforward terms. Can she find the shortest, most direct path between points A and B?

Consider a business analyst. I read the documentation he creates. That tells me if he simply knows the business or if he indeed is good at observation and analysis. Does he see only the surface of things, or can he lift the hood, and identify the patterns and sub-structure that the surface covers? I will know if his communication skills are adequate. Can he accurately, clearly, describe what the business is, and what they are asking for? The more I know the business (agility) the easier this gets.

I use the applications that they specify and build. I know if they have empathy. Do they know their users? Can they walk in the user’s shoes?

I watch how they negotiate one on one conversations, and meetings. This tells me if they know how to listen.

You get the idea. Every little thing that a person does is a breadcrumb I can follow, especially if I know how to do that work myself (agility).

My recommendation – chuck it

If at all, only the bean counters need to worry about whether a piece of work is a bug or an improvement. Hide this question from the people that actually do the work. This question is irrelevant to the conduct of the work. If you hear someone in your development team kvetching about bugs and improvements, make them buy lunch for the whole team (agility).